Soweto, South Africa – Less than seven miles from the carefully crafted glitter of Soccer City, the host complex for the World Cup, two legendary South African football players told fascinating often fearsome stories that powerful people want suppressed.

Two days before the recent World Cup championship match won by Spain “Smiley” Moosa and Nkosi Molala spoke at a community center in Soweto discussing their lives under apartheid and that ugly era’s lingering legacy on South African society.

Moosa and Molala both made their marks on South African soccer in the 1970s.

Under apartheid’s rigid racial categories Moosa carried the classification of Indian while Molala was African – designations barring these talented players from South Africa’s then whites-only national team.

Moosa holds the distinction of being the first non-white ever to play for an all-white soccer club in South Africa.

Moosa’s skills and light skin color earned him that short-lived elevation, later snatched back by apartheid restrictions. Continuing discriminatory practices caused Moosa to file a lawsuit against horse racing authorities where he now works as a race announcer.

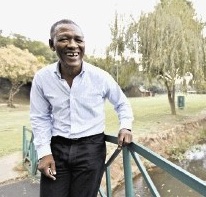

Nkosi Molala, South African soccer hero, apartheid fighter

Nkosi Molala, South African soccer hero, apartheid fighter

Molala, lauded for his fancy footwork, holds the distinction of being the first South African soccer star ever imprisoned for political reasons.

Molala spent seven years in the infamous Robben Island prison that held Nelson Mandela, South Africa’s first black president and Jacob Zuma, that nation’s current president. Molala lost an eye during an assault by South African police following his 1985 prison release, effectively ending his soccer playing career.

Despite their once star-status Moosa and Molala both said they have been excluded from the World Cup spotlight that has raised the international stature of South Africa, the first African country to host the Cup since the inception of that international event in 1930.

“We are the pioneers and we are pushed aside,” said Moosa, whose professional soccer career began at age 16 and lasted until he was 39.

Molala noted philosophically that, “History is always the history of those in charge. It is so political.”

Moosa and Molala, both in their late fifties, remain active in the sport that defined their lives.

Moosa, a critic of the caliber of soccer in South Africa today, coaches and often plays soccer outshining players half his age.

One of Molala’s many endeavors is training inmates to be soccer referees, an anti-crime initiative for both the prisoners and underprivileged youths they would work with.

Moosa and Molala both spoke on a panel entitled “Football, Sport, Memory, and Apartheid” one of a series of forums sponsored by the Khulumani Support Group examining how the mega-bucks benefits from the World Cup are by-passing impoverished South Africans. The Methodist Central Mission in the Jabavu section of the sprawling Soweto Township located outside Johannesburg served as the site for these forums.

South Africa’s Minister of Finance, Pravin Gordham, boasted in a widely published June 2010 newspaper commentary that low-income families received wages totaling 7.3 percent of his government’s $227-million investment in World Cup thanks to projects upgrading the transportation and telecommunication infrastructures “…therefore contributing to reduction in poverty.”

However, according to another panel participant, Gordham’s view is challenged by people on the lowest rungs of South Africa’s economic ladder where some non-white communities ringing prosperous urban areas remain without electricity and rely on communal toilets.

“The World Cup has robbed many of us. It only speaks to a selected few. South Africa’s Soccer Team players get [big salaries] while people in the streets need food and money for electricity,” said Tapuwa Moore, an actress, gender activist, poet and the coach of the Forum for the Empowerment of Women soccer team.

Many inside and outside South Africa viewed the Cup as an opportunity for creating lasting interracial unity in the post-apartheid era but some like Moore are skeptical.

“If this unity can stop discrimination then soccer will be beneficial.”

Hassen Lorgat, moderator of the panel and organizer of the Khulumani series, framed the “Football, Sport” presentation by reminding those in attendance that people used all kinds of weapons to battle against apartheid.

“Some people fought with rocks and guns. Some fought with music and poetry. Some fought with football,” said Lorgat, a respected soccer player during his youth. People inside and outside of South Africa supported sports boycotts as a method to pressure that nation to end apartheid.

Nkosi Molala’s fight against apartheid began with an emotionally jarring 1974 incident when he was a member of South Africa’s blacks-only national team. This incident occurred during a trip to Rhodesia, a then white-minority-ruled/apartheid-policy nation north of South Africa.

While riding a bus to play Rhodesia’s national black team Molala said a person came up to the bus and asked why they were in Rhodesia. When he said they came to play soccer the person told him the Rhodesian team had fled the country and it’s members were fighting in the war against minority rule.

“That encounter opened my eyes and changed my life. One event can do that. I wasn’t political before that. When I came back to South Africa I became involved with politics,” Molala recounted.

Molala’s anti-apartheid activism led to numerous arrests, beatings, torture and eventual imprisonment on Robben Island convicted for sabotage.

A year after his 1985 release from Robben Island Molala helped form the Soccer Players Union of South Africa. A lawsuit filed by that trade union to secure withheld wages for one black team led to a brutal confrontation with police.

“The police killed fourteen people during our protest outside a courthouse. We held a funeral for those killed and did it following the proper rules police and soldiers still surrounded us and attacked. I was hit in the chest with a tear gas canister and I lost an eye,” said Molala, who serves as a ranking official with the South African National Council for the Blind and the politically active Azanian People’s Organization (AZAPU).

In July 2010 a major South African newspaper ranked “Smiley” Moosa was one of that nation’s Ten Best Players of All Time. When Moosa played briefly for the all-white Berea Park team he had to use the name Arthur Williams because his real name easily revealed his non-white identity.

“When I went to Berea Park it was the first time I had a dressing room and it was the first time I played on grass. Our grounds were rocky or sandy. I came from a squatter’s camp to a palace,” recalled Moosa who also played in England.

“We players saw each other as players…not color. The system was so inhumane to keep us separate,” Moosa said adding with a chuckle, “When I was growing up, if somebody said South Africa would host a World Cup in 2010 I would say send them to the mental institution.”